Sillar, silence and Seville

This next installment of notes from the driver’s seat results from our time in Arequipa, where I was writing the last piece on Andean cosmology and experienced a shock realisation of how this cosmology was harnessed and transformed in the Colonial period by Spanish Catholicism. And perhaps more importantly, how this theological conquest can be read in the colonial architecture itself.

From a bustling, chaotic outside world one steps through into a sublime plaza

In my earlier post, the pachas—hanan, kay, uku—were presented as lived orientations, disclosed in environment, labour, and time. The axis mundi there was not some pillar driven into the earth, but a moment of conjunction: a fleeting coherence in which worlds touched and briefly held in a perceivable way. What changes with the arrival of Spanish Catholicism is not the need for an axis, but its grammar. The question becomes how transcendence is experienced, disciplined, and made inhabitable when imported theology encounters this millenia-old vertical Andean cosmos.

The neoclassical Basilica Catedral de Santa Maria (1540) on the Plaza de Armas in Arequipa

In Arequipa, that encounter does not resolve itself in synthesis so much as in overlay. The city itself is built of sillar, volcanic stone quarried from the flanks of El Misti, Chachani, and Pichu Pichu—mountains that already functioned as apus, vertical interlocutors between worlds. Upon this lithic ground, the Spanish Counter-Reformation inscribed a different axis, one no less vertical, but now explicitly moral, sacramental, and Marian. The Monasterio de Santa Catalina de Siena is among the clearest expressions of this reorientation.

Arequipa is overlooked by three sacred volcanos, apus, locations for child sacrifice in the Incan period

Founded in 1579, barely four decades after the Spanish consolidation of the region, Santa Catalina was not conceived as a marginal or ascetic outpost. It was endowed from the beginning as a cloister for the daughters of Arequipa’s elite Spanish families, a place where wealth, lineage, and orthodoxy could be conserved under the guise of renunciation. Entrance required a substantial dowry. Cells were privately owned and lavishly furnished. Servants—often Indigenous or mestiza women—lived inside the enclosure to maintain the domestic lives of the nuns. Far from retreating from the world, the monastery reproduced it in miniature, sealed and purified.

Lanes in the sprawling monastery are named for cities in Southern Spain - Toledo, Córdoba, Málaga, Sevillá

This matters, because Counter-Reformation theology was never primarily about interior belief. It was about order made visible. After Trent, Catholicism asserted itself through spatial discipline: enclosure, procession, inscription, repetition. Orthodoxy had to be walked, seen, touched. In the Andes, where cosmological meaning was already spatial and embodied, this approach proved unusually effective.

On a daily basis, nuns (in this case novices) perform a processional walking rosary, circumambulating a peaceful courtyard

Within Santa Catalina, the cloister is not merely an architectural feature; it is a cosmological device. Movement is restricted, repetitive, circular. The sky is framed by corridors. Silence is imposed, not as absence, but as a medium. Life unfolds in a permanent kay pacha stripped of contingency. The world beyond the walls—markets, earthquakes, rebellions, republics—exists only as distant echo.

Calle Sevilla is a long way from the world outside, but this was a home for educated, well-connected women who knew much about the world

That is not to say that this is a world cut off. Daughters of wealthy families, nuns within Santa Catalina’s walls were waited on by slaves who could exit the cloister as required, being not bound by the papal enclosure. They enjoyed spacious, austere yet comfortable apartments furnished in the Andalucian style.

Room of a high-status resident

It is here that Marian theology becomes decisive.

The Counter-Reformation elevated Mary not simply as an intercessor, but as the perfected creature, untouched by original disorder. Long before the dogma of the Immaculate Conception was proclaimed in Rome, Spanish Catholicism treated it as settled truth. To assert that Mary lived sin mancha ni deudo de pecado original was to affirm that purity was not merely aspirational, but historically instantiated. A human life, once, had aligned perfectly with divine order.

In the Andes, this claim carried unexpected resonance. Indigenous cosmologies had long understood disorder not as guilt, but as imbalance, contamination, or debt. Ritual life was oriented toward restoring equilibrium between realms. Marian purity, articulated in Counter-Reformation terms, thus offered a new axis mundi: not a mountain or a tree, but a body through which perfect alignment had passed.

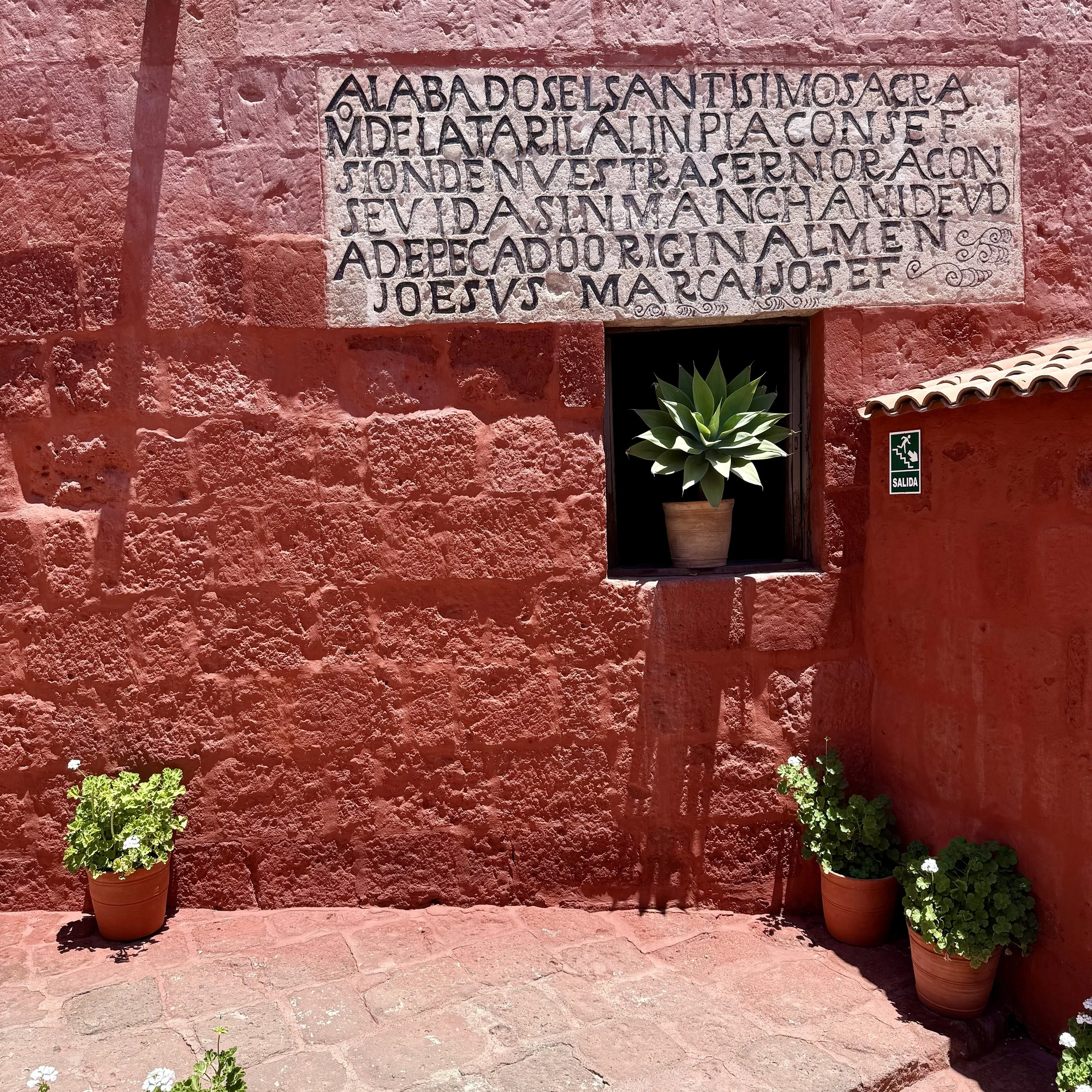

The inscription at Santa Catalina makes this explicit. Set into the monastery’s wall, it declares:

ALABADO EL SANTÍSIMO SACRAMENTO DE LA TARILLA LIMPIA CONCEPCIÓN DE NUESTRA SEÑORA, CON SU VIDA SIN MANCHA NI DEUDO A DE PECADO ORIGINAL. MEJORES MARCA JOSÉ F.

Praised be the Most Holy Sacrament. Of the pure and immaculate conception of Our Lady with her life without stain or debt of original sin. Marked / commissioned by José F.

After the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, the Catholic Church confronted two destabilising challenges: the denial of the real presence in the Eucharist and the rejection of Marian doctrines as unscriptural excesses. The Counter-Reformation response was therefore not confined to councils and catechisms, but unfolded materially and spatially. Belief had to be made visible, repeatable, and unavoidable—embedded in stone inscriptions, public walls, processional routes, and the constant circulation of formulas of praise. Doctrine was no longer merely taught; it was built. What appears as ornament or piety is, in fact, theology fixed into the architecture of the New World, where associated ritual traditions such as processional routes are energetically preserved to this day.

The inscription at Santa Catalina is a prominent attestation of principles assailed in Europe during the Reformation

This was a way ‘stabilising’ the ecclesial order upended by the Protestant Reformation in Europe, and by this synthesis with diverse cosmological traditions in the New World.

Yet this stabilisation is not abstract. It is lived through enclosure, through renunciation performed by women whose bodies themselves become sites of doctrinal meaning.

The daughters of wealthy families who entered Santa Catalina did not simply withdraw from society; they enacted a Marian imitation. Virginal, enclosed, obedient, they became living extensions of the theology inscribed on the walls. Their cloistered existence was not marginal to the colonial order—it was central to its moral economy. It is an extraordinary social technology with curious echoes of the Arab Islamic tradition woven through the culture of Al-Andalus.

Nuns socialised around a central well and an adjacent bathhouse, the monastery a bulwark of peace in a violent time in history

Here the existential dimension sharpens. Heidegger reminds us that meaning discloses itself not in doctrine, but in being-in-the-world. At Santa Catalina, being-in-the-world is radically constrained, but not emptied. On the contrary, the restriction intensifies presence. Every step along the cloistered corridors, every glance upward to the framed sky, every repetition of prayer becomes an enactment of alignment. The axis mundi is no longer distant; it is momentary, fragile, embodied by practice. At a practical level, social obligation was enacted in the good deeds of the nuns: baking bread for the poor daily in a large bakery; preparing the eucharist for local churches.

A life of obligation: Nuns prepared bread daily for distribution to the poor

This is where the Andean inheritance quietly persists. Despite the theological absolutism of the Counter-Reformation, the lived experience of the monastery resonates uncannily with earlier Andean and Andalucian understandings. The cloister functions as a controlled kay pacha, sealed against the contaminations of the outside. Mary operates as a mediating figure, absorbing disorder without being marked by it. Stone, earth, and silence remain central. The world is not transcended so much as carefully balanced.

Prominent nuns are remembered for their dedication and piety long after their death

Thus, the axis mundi in colonial Peru is neither purely European nor purely Indigenous. It is re-expressed through Marian theology, preserved by Spanish émigrés anxious to reproduce orthodoxy at the empire’s edge, but it is lived in a landscape that never fully relinquishes its vertical imagination. At Santa Catalina, transcendence does not thunder from heaven; it settles into courtyards, corridors, ceilings and inscriptions. In colour and calm spaces. It appears, briefly, in the existential moment when order holds—when the worlds align in silence—before the bell rings and the circle begins again, a cycle until death and beyond.

Fascinating stuff, ingenious in it’s subtlety and, for a secularist, laden with insight about our ontic condition absent of equivalent ontological claims.